“Those whose identities are rarely questioned and who have never known exile or subjugation of land and culture,” wrote Anthony D. Smith, Professor Emeritus of Nationalism and Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, “have little need to trace their ‘roots’ to establish a unique and recognizable identity.”

Which should help to explain the Jewish concern for roots. The stories found in Genesis chapters 12 to 50 aim at satisfying the need for origins, history, and the belief in destiny, cultural individuality, and unique collective solidarity. These chapters also testify that Judaism does not begin with religion but with peoplehood.

Though the foundational literature of the Jewish people, the TaNaKh, places the origin of Israel’s relation with God in patriarchal times, there is—in the words of the late professor Nahum Sarna—a glaring contradiction between patriarchal customs and Torah legislation.

The Genesis stories, says Alan M. Dershowitz—a prominent scholar on United States constitutional and criminal law—take place before the advent of formal law rules. As a result, the heroes and heroines must make tragic choices, balancing lesser evils against greater evils without the benefit of legislation.

In witnessing the fact that Judaism’s cultural roots were older than their religion, the book of Genesis argues for Judaism as different from life legislated by religious codes. True, Abraham’s stand transcended the actual needs of each day’s life and stretched into the distant future: his life was conducted with full consciousness of having a destiny. Concern with transcendence, however, is a long way from a Judaism ruled by medieval codes of Jewish law.

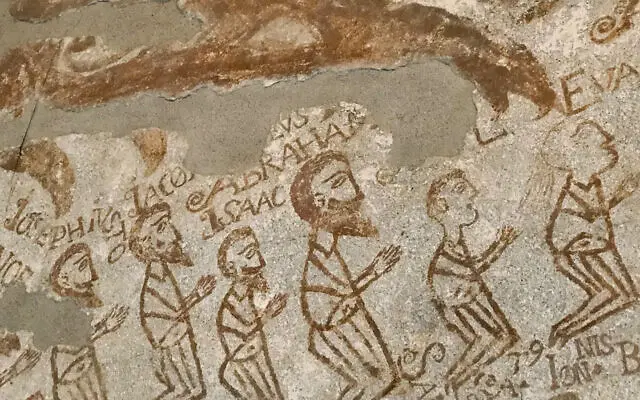

Abraham’s life and acts are not religious but cultural and historical. He was born in Ur; he lived in Harran; he worked and married; these and other events in the text do not mark the life of a man for whom worshipping is the end of life. He does not pray; he does not observe rituals. The TaNaKh simply depicts him as a moral man. He pursues peace, is generous and hospitable, and intercedes on behalf of even the evilest of people.

What we learn from the patriarchs, beginning with Abraham, is that Judaism didn’t suddenly spring up as the complex of beliefs and religious practices we have today.

There are historical reasons why Judaism took the shape it has today, but that has nothing to do with what Judaism is meant to be, something that the Abraham stories intend to show. The book of Genesis argues for the foundations of the people of Israel, not for a fixed complex of rituals and life-regulating laws.

The one described so sympathetically in the TaNaKh within human weaknesses is celebrated as the embodiment of the blessing on ‘all the nations upon the earth’, which his descendants had only to imitate.

And I will make you a great nation, and I will bless you and make your name great, and you shall be a blessing. And I will bless those who bless you, and those who damn you I will curse, and all the families of the earth through you shall be blessed.”

Bereshit 12:2-3