It has often been said that Gen. 22 is one of the most beautiful narratives in the Jewish Foundational Literature, one that also has a particularly special place among the narratives of world literature. It also generates one of the most puzzling issues facing religious and moral societies.

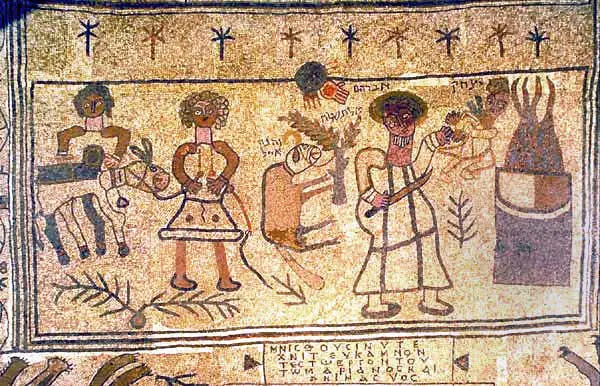

This is a tale about God testing (Hebrew= nisah) Abraham, the first of Israel’s patriarchs, by commanding him to sacrifice his beloved son, Isaac. Just when Abraham is at the point of executing the dreadful order, an angel calls him to stop, “because now I see that you are a God-fearing person and would not withhold your son… from Me” (Gen. 22:12).

The readers, though, have been informed from the very start of the tale that God is only testing (nisah) Abraham, that He never really intended to have Abraham’s son killed. The purpose of the tale is centered on the “test.”

Carmy Shalom and David Shatz of the Department of Judaic Studies and Philosophy at Orthodox Yeshiva University in New York comment that

In his brilliant “dialectical lyric” Fear and Trembling, the nineteenth-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard advanced a reading of the “sacrifice of Isaac” (the akedah, as it is called in Hebrew) that has dominated interpretations of the episode ever since. Abraham is the “knight of faith,” whose greatness consists in obeying God … Abraham was prepared to commit an act whose religious description is “sacrifice,” though its ethical description is “murder.” … Kierkegaard recognizes the possibility of conflict between divine commands and morality and asserts the supremacy of religious faith in all such situations.

Immanuel Kant, widely considered one of the central and most influential figures of modern philosophy, took a more daring position by asserting that

“There are certain cases in which a man can be convinced that it cannot be God whose voice he thinks he hears: when the voice commands him to do what is opposed to the moral law...”

Kant is convinced that this command to kill cannot have come from God because God cannot contradict His moral law that commands not to kill.

Echoing these philosophical ruminations, conservative rabbi Elliot N. Dorff, professor of Jewish theology at the American Jewish University in California, agrees that

“… some passages in the Bible are morally ambiguous at best and downright immoral at worst—texts such as God’s command to bind and presumably murder Isaac [Genesis 22],...”

Fearlessly, Kant wastes no more time; he maintains that Abraham’s correct response to the voice from heaven should have been

“That I ought not to kill my good son is quite certain. But that you, this apparition, are God—of that I am not certain, and never can be …”

Though Abraham is lauded in the Biblical text, the fact remains that he failed the test of recognizing that his case was not different from when he interpellated God in Genesis Chapter 18 about the justice of destroying Sodom and Gomorrah.

What the foundational literature of Israel teaches in the end is that there is an ethics to which even God has to submit, for if he does not, he would be guilty of injustice.