Chapter 16 of Bamidbar (the book of Numbers) registers what the Jewish foundational literature considers one of the most subversive moments in the long series of protests of Israel against Moses in the wilderness.

A confrontational Levite by the name of Korah, together with a number of followers, questions Moses and Aaron’s authority:

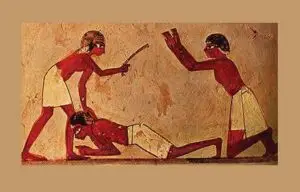

“They combined against Moses and Aaron and said to them, “You have gone too far! For all the community are holy, all of them, and the Lord is in their midst. Why then do you raise yourselves above the Lord’s congregation?” (Bamidbar 16:3). The episode culminates with Korah and his cohorts’ total annihilation: “And the earth opened its mouth and swallowed them up, and their houses, and all the men that appertained unto Korah (ibid. 16:32).

The rebels argument was that not only the priests but the entire community was holy. Given that the Book of Exodus had previously declared that “you shall be unto Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation,” it seems difficult to find fault in what Korah and his followers are saying. It is even more difficult to find justification in the lethal response it elicited.

Rabbinism doesn’t look at history to explain why situations like this one happen. Instead, the Mishnah states:

Every controversy that is for the sake of heaven will endure, but one that is not for the sake of heaven will not endure. What is a controversy... not for the sake of heaven? The controversy of Korah and his company"

To argue is acceptable, the rabbis seem to be saying; what may be objectionable is the motivation. The rabbinic assumption is that Korah and his group are not motivated by the interests of the people of Israel.

What is at stake here is, in fact, a disagreement between two theological camps over the holiness of the people. According to some modern commentators, Numbers 16 is “part of a broad debate about Israel’s identity.”

In Devarim (Deuteronomy), the last of the five books of the Torah and the one that follows Numbers, we read:

For you are a people holy to the Lord your God; the Lord your God has chosen you to be a people for his own possession, out of all the peoples that are on the face of the earth.

(Devarim 7:6)

The three terms used for Israel’s relationship with God in this verse—holy, chosen, and possession—speak to the corporate identity of Israel. These are issues that occupy us today as much as they did the wilderness generations. Thus, in large part, the relevance of this passage in Israel’s foundational literature.

The above verse in Deuteronomy is dependent on an earlier passage in the second book of the Torah, the book of Shemot (Exodus) 19:5-6: “if you will obey me…you shall be my treasured possession from among all the peoples…you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.”

A significant difference exists in the notion of the chosenness of the Jewish people between the book of Shemot and Devarim.

In Shemot, holiness signifies the unique merit and privilege of Israel. In contrast, Devarim, which embraces the concept of Israel’s merit and unique worth, elaborated on this idea and established it as the foundation for the need to perform duties to God. In other words, the elevated position conferred on Israel is not only a privilege, but it also entails a duty.

The holiness of the Jewish people is not a reality but rather a goal. The Judaism of Moses is arduous. It means knowing that we are not a holy people. Korah’s Judaism is easy. It allows every Jew to be proud and boast that he is a member of the holy people, which is holy by its very nature. This obligates him to nothing.

The late Israeli professor Yeshayahu Leibowitz points out that there is no greater opposition than that between the conception of Am Segulah (a chosen people) as implying subjection to an obligation and Am Segulah as purely a privilege. The people of Israel, says Professor Leibowitz, were not the chosen people but were commanded to be the chosen people.

In Korah’s thought, says the professor, religious faith and national arrogance are fused, at times even with racist ingredients. You yourselves, says the “great intellectual maverick of Israeli Orthodoxy,” are not holy, but the task eternally to strive toward holiness is laid upon you.”