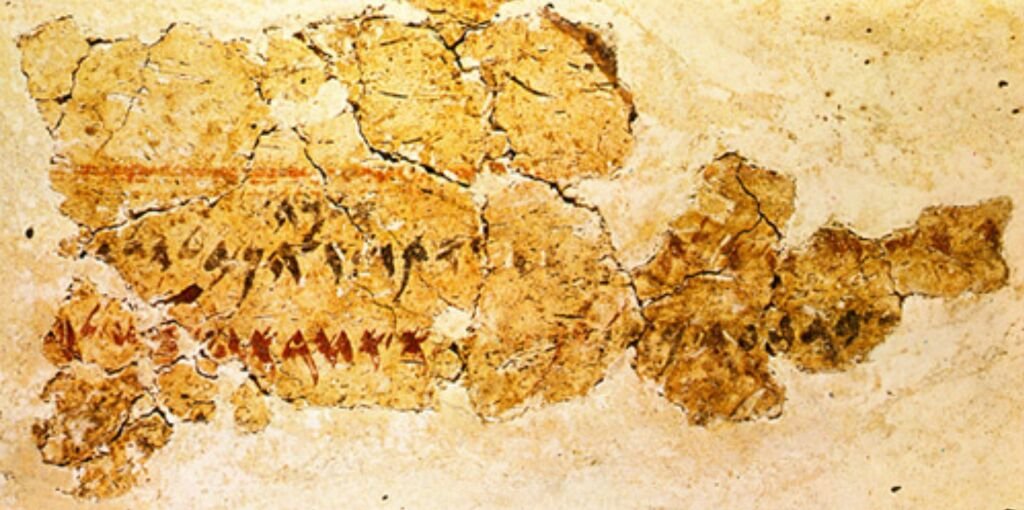

Portion of the Deir Alla inscription that mentions Balaam Amman Museum

In 1967, during excavations of a building at Deir Alla in the Jordan Valley, a Dutch archaeological expedition uncovered the fragmented text of a tale centered on the visions of a seer of the gods, Balaam, son of Beor. This name is familiar to readers of the TaNaKh as he is one of the main protagonists of chapters 22-24 of the Book of Numbers.

The biblical narrative, confirmed by the Deir Alla discovery, forms part of an ancient way of telling stories about prophets or holy men who blessed and cursed nations and their kings.

The Book of Numbers tells us that a Moabite king, fearful that the Israelites on their way to the Promised Land would ‘encircle’ Moab, depriving them of any possibility of expansion, dispatches repeated missions to Balaam.

Balaam is a man whose word (of blessing or curse) was regarded as endowed with an infallibly effective ‘power.’

In his pagan naivete, the Moabite king believed that Balaam could cast a spell on Israel. As he says to him, “What you bless is blessed, and what you curse is cursed.”

In spite of his having been promised great wealth, Balaam persists in refusing to accompany the king’s emissaries, insisting that God’s authority binds him. Eventually, God appears to Balaam and grants him permission to accompany them, but with the admonition to do only what he is told by God.

The words coming out of Balaam’s mouth are the ones dictated by God. Instead of cursing the Israelites, Balaam blessed them and extolled their might, acknowledging that they are a blessed nation.

The premise of the narrative is that Israel’s God controlled all Balaam’s activities. For Paganism, on the contrary, divine powers can be manipulated by a caste of professionals through a set of carefully prescribed procedures.

A prophet, seer, or simple visionary, on the other hand, is someone who “sees” things as they are and cannot but call them by their authentic name. Professor Alter notes, “The very first word in the Hebrew of the Balaam story is the verb ‘to see,’ which appropriately becomes, with some synonyms, the leading word in this tale about the nature of vision.

Gazing down at the Israelite encampment from mountain tops, Balaam is overwhelmed by Israel’s might, encamped on its own, without allies from other nations in attendance. He had no choice but to conclude that this was not a people meted out for curses and doom but rather one that had been blessed.

Yes, the story is part of the folklore of the area, but it also belongs to the particular wisdom bequeathed by Israel in its “by-the-way” definition of truth and lies: you cannot say something about somebody that is not; nor can you avoid acknowledging what is there to be seen.

Call it the word of God.