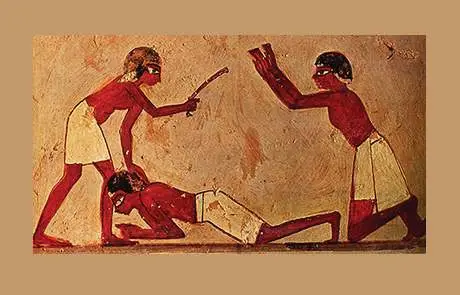

The hardening of Pharaoh’s heart in Shemot ( Book of Exodus) is often misunderstood as a theological problem.

If God hardens Pharaoh’s heart, how can Pharaoh be held responsible?

Read this way, the text appears to undermine moral agency. Read carefully, it does the opposite. It offers one of the Torah’s most severe warnings about power, responsibility, and the conditions under which freedom collapses.

The narrative unfolds in stages. At first, Pharaoh hardens his own heart. He resists, delays, bargains. Later, his heart “becomes hardened.” Resistance turns into habit. Only then does the Torah say that God hardens Pharaoh’s heart. This is not divine interference. It is moral confirmation. Pharaoh’s freedom is not revoked; it is exhausted.

The Hebrew language is precise. The verb most often used—ḥ-z-q, to strengthen or make rigid—does not describe emotional cruelty. It describes rigidity. Pharaoh does not lack information. He sees suffering. He recognizes consequences. What he loses is responsiveness. His heart no longer bends.

This is the Torah’s unsettling claim: moral failure does not begin in ignorance or malice. It begins when responsibility is repeatedly refused. Over time, the capacity to respond erodes. Choice remains in theory, but not in practice. Freedom fossilizes.

Pharaoh’s crime is not simply oppression. It is sovereignty without answerability. He rules without bearing the consequences of his decisions. Suffering is externalized. Responsibility is deferred. Power continues to act even when judgment has disappeared. This is why the plagues escalate. They are not meant to persuade Pharaoh intellectually. They are meant to shatter the illusion that power can operate without responsibility.

By the end, Pharaoh no longer chooses freshly. He persists. He continues because stopping would require acknowledging what has already been done. Evil here is not driven by desire but by inertia. This is moral irreversibility: when wrongdoing continues because responsibility has been postponed too long to reclaim.

Judaism names the opposite posture with a single word: Hineni—“Here I am.” To say Hineni is not to claim certainty or control. It is to place oneself within the chain of responsibility. Abraham, Moses, Isaiah all say Hineni before knowing the full cost. Pharaoh never does. He demands control without responsibility—and loses both.

This ancient narrative is not about a tyrant alone. It is about systems of power. Institutions, political leaders, harden the same way hearts do: harm becomes normalized, escalation becomes automatic, responsibility diffuses. Decisions continue not because they are right, but because stopping would require ownership.

This is why the story is painfully contemporary. Automated systems and algorithmic authorities do not harden emotionally. They harden structurally. They optimize, reinforce, and escalate without moral interruption. Unlike Pharaoh, machines never possessed the capacity to say Hineni. They cannot repent. They cannot soften. When judgment is ceded entirely to systems that cannot respond, hardening becomes inevitable.

Against this, the Jewish tradition insists that wisdom must remain answerable. Pirkei Avot 6:6 teaches that Torah is acquired not through brilliance or power, but through humility, restraint, deliberation, and faithful transmission—qualities designed to keep knowledge bound to human responsibility.

The hardening of Pharaoh’s heart is therefore not a story about divine coercion. It is a warning. When power repeatedly refuses responsibility, freedom does not disappear. It solidifies. Authority persists without the capacity to stop itself.

The question Exodus leaves us with is not whether intelligence can grow without limits. It is whether human beings will remain present enough to say Hineni before systems—political, institutional, or technological—harden beyond interruption.

Rabbi Moshe Pitchon is the author of

Judaism and Artificial Intelligence: Dignity and Moral Responsibility, (English and Spanish, Amazon)

Appearing in the first week of February 2026—a work on power, judgment, and the limits of intelligence without responsibility.

“Your Israel chapter is far better than most treatments by sympathetic Jewish thinkers and far more honest than most hostile ones. You neither exempt Israel nor single it out.

You frame sovereignty as a burden of agency, not a moral credential or a stain. “That position will unsettle many readers—which is exactly why it is philosophically correct