The Hanging Threat of Chaos

The creation story in the first chapters of the Torah would be misunderstood if read simply as an intended report of an event that happened at the beginning of time.

A half-baked reading of the first chapter of Bereshit—the Book of Genesis, the first book of the Torah—tells that before the first words of creation were spoken, there was

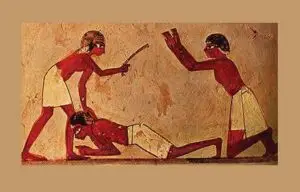

(tohu va bohu) vacuity, confusion: “a formless void:” Chaos.

Accordingly, the material out of which the world was created was unlivable. Sub-animals may make do with an environment, no matter how chaotic. On the other hand, humans need a world to live in, which the Greeks termed a “kósmos,” a harmonious and ordered universe. To the Greeks, the world was like, for us, a tidy room where everything should be in its proper place.

Hand in hand with this image that the first chapter of Bereshit wants us to picture, there’s the hint that creating an ordered universe out of primordial chaos is not enough. “Creation” refers to the start of an ongoing process rather than its conclusion.

A constant flow of creativity keeps the world from chaos to re-inserts itself.

Rabbi David Kimhi (Radak), a 13th-century biblical commentator, reads the verse in Bereshit (Genesis),

“God ceased from all the work of creation that He had done” as

“God ceased the work of creation for human beings to continue it.”

This perspective on life is especially relevant right now.

At the conclusion of the Succoth festival, we begin the annual cycle of reading the Torah anew. This time, we do it reflecting on the turmoil that looms around us.

A year ago, the orderly planet was overrun by chaos. The word used was less scientific, less Greek; a Russian word made us shudder: “pogrom.”

People who are incapable of telling one river from another or one sea from another opt to ignore the pogroms—the chaos—which, according to them, certain human beings are entitled to bring upon others. According to these feeble-minded people, the ensuing self-inflicted chaos afflicting them is genocide, which is what Jews assumedly commit when they attempt to stop the daily barrage of rockets and ballistic missiles that are hurled at them in an attempt to determine how many lives they can claim.

What have Hamas, Hizbullah, the Houthis, and Iran ever done for their people other than bring upon them squalid living quarters, misery, poverty, discrimination, and death?

To put it as benignly as possible, chaos is nothing but the result of human short-sightedness, both from the leaders and those who allow them to lead.

The Jewish view of the world is not one of a confrontation between forces of darkness and light, goodness and evil, but of creativity and chaos. Not surprisingly, Jews and their institutions are so overrepresented around the world in their dedication to medicine, science, technology, law, finances, and education, and now, even an army trying to establish order where chaos wants to reign.

The Torah begins with a possibility, a task, and a warning. This formula is called Judaism, but in fact, it is about life.

Appropriately, the fifth book of the Torah (Devarim-Deuteronomy) closes the idea it wrote at the beginning of the first book (Bereshit), saying

“I call heaven and earth as witnesses! Before you, I have placed life and death, the blessing and the curse. You must choose life so that you and your descendants will survive.”

Share:

More Posts

What Are Values — and Why They Matter Now More Than Ever

We speak often about values. Political leaders invoke them. Institutions advertise them. Corporations display them on websites. Universities promise to teach them. Yet rarely do

The Hardening of the Heart

The hardening of Pharaoh’s heart in Shemot ( Book of Exodus) is often misunderstood as a theological problem. If God hardens Pharaoh’s heart, how can Pharaoh be

Israel on the Threshold of Jewish Moral History

In Judaism, justice is not a concept; it is a legal demand. Compassion is not a sentiment; it is a regulated practice. Guilt is not

Memory is Not Victimhood

Jewish cemeteries are often called Beit HaChayim—the House of the Living. That phrase is a rebuke. Judaism refuses to define identity through death, suffering, or