On the surface the book of Bamidbar (Numbers) seems rather dull and incapable of telling much that is of value to contemporary lives.

Chapters 1 to 4—this week’s reading—for instance, are, at first glance, a classification of Israel’s tribes and the cultic duties of the Levites with regard to the external care of the sanctuary.

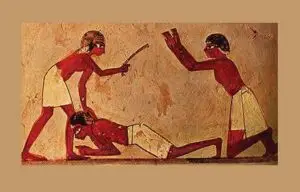

These internal administrative generational tasks, assumedly, took place some 3000 years ago in the wilderness of Sinai, on the way from Egypt to the Promised Land.

The primary concern of Bamidbar, is about the origin and singularity of Israel. The issue, then, is one of identity: who is Israel?

In taking a census, the Book of Numbers counts “the whole Israelite assembly,” not Israel but the “assembly of the children of Israel.” By combining two separate terms of reference, “children of Israel” and “assembly” (Adat and Beney Israel), Numbers defines Israel as those who had associated themselves by agreeing to the terms of the covenant made at Sinai.

The Book of Exodus reported that together with the “Children of Israel,” a “mixed multitude went up also with them.” And the Book of Deuteronomy notes that concluding the covenant at the foot of Mount Sinai bound them together; besides “your little ones, your wives,” stood “your stranger who is in your camp.”

Strictly speaking, then, it is more than the blood descendants of the twelve sons of the patriarch Jacob that constitute “Israel.” As Professor Jacob Neusner points out, the demonstrative is that “Israel” encompasses those born into the people and those that join the people by choice.”

Chapters 1 to 4, for instance, are, at first glance, a classification of Israel’s tribes and the cultic duties of the Levites with regard to the external care of the sanctuary.

These internal administrative generational tasks, assumedly, took place some 3000 years ago in the wilderness of Sinai, on the way from Egypt to the Promised Land.

The primary concern of Bamidbar, is about the origin and singularity of Israel. The issue, then, is one of identity: who is Israel?

In taking a census, the Book of Numbers counts “the whole Israelite assembly,” not Israel but the “assembly of the children of Israel.” By combining two separate terms of reference, “children of Israel” and “assembly” (Adat and Beney Israel), Numbers defines Israel as those who had associated themselves by agreeing to the terms of the covenant made at Sinai.

The Book of Exodus reported that together with the “Children of Israel,” a “mixed multitude went up also with them.” And the Book of Deuteronomy notes that concluding the covenant at the foot of Mount Sinai bound them together; besides “your little ones, your wives,” stood “your stranger who is in your camp.”

Strictly speaking, then, it is more than the blood descendants of the twelve sons of the patriarch Jacob that constitute “Israel.” As Professor Jacob Neusner points out, the demonstrative is that “Israel” encompasses those born into the people and those that join the people by choice.”

Israel is, accordingly, the name of a society that believes itself to stand in a special, intimate relationship to God, and which believes that that relationship is not the result of its choice but of God’s.”

Robert C. Dentan,

Life is a series of responses. The difference between being driven and choosing the kind of response and to what or whom one is responding is what makes a life human. Those who associate themselves to respond to life according to the understandings of “beney Israel” are Jews. Understandings may, for the sake of expediency, be translated into laws or commandments. The point, however, is that “understandings” come first and are more pristine. That’s why after encapsulating in one single formula what Judaism is all about, the first-century Jewish sage Hillel the Elder didn’t say, “Now go and observe laws,” but “Now go and learn.”

Israel is not the assembly of those who observe laws but those who assemble to find together the responses to the challenges of the hour.

The philosopher Soren Kierkegaard once said:

“Whatever the one generation may learn from the other, that which is genuinely human no generation learns from a previous one. In this respect, every generation begins primitively, has no other task than each previous generation, and advances no further … This genuinely human quality is passion, in which the one generation perfectly understands the other and understands itself as well. Thus no generation has learned from another to love, no generation begins at any other point than at the beginning, and no generation has a shorter task assigned to it than had the previous generation...”

Soren Kierkegaard

In a less elaborated form but undoubtedly in the same spirit, Jewish sages have stated that every generation stands anew, as it were, at the foot of Mount Sinai.